It was a fine thing for Jack to ask his fans to forget about his film career, it's another for us to obey. I had already seen To Be or Not to Be by the time I read the biography, but I went on to see two more of his pictures. The Meanest Man in the World was undistinguished, but not too bad and at least had some choice lines for Eddie Anderson. On the other hand, Buck Benny Rides Again was about as close as a movie could come to Jack's radio program, with almost every cast member and even an audio-only Fred Allen putting in appearances; and yet, Buck Benny didn't quite satisfy me. It's a neat curio, but felt "off," just as I find his television programs don't entirely click with me.

Perhaps I should have stopped questing for Jack's films then and there, but within the last week I watched three more of them. Having done so, I feel compelled to share what I learned; hey, you don't have anything better to read, right?

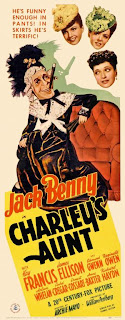

Charley's Aunt (1941) came up in scattered references via Jack's radio show, even post-war. It's just one of several film adaptations of a then-popular play, but as I have familiarity with the play, it was as good as new to me. Jack is an English university lad (who's spent 10 years in school) whose roommate Charley asks to pose as his wealthy aunt so Charley and another friend have a chaperone for their dates on the day they each intend to propose. Charley's real aunt turns up as well, using a false identity for her own reasons. So, it's a farce, basically looking for an excuse to get a man to wear drag. It also features Edmund Gwenn as the guardian of the two young ladies; Gwenn needs to give his consent for them to marry, so Jack's character is encouraged to woo him into writing his consent. It brings to mind Gwenn's alleged deathbed quote, "Dying is hard; but not as hard as comedy."

Because Jack's character spends most of the picture in drag, he's given very masculine characteristics, notably being a boozer and womanizer. This is very odd for a Jack Benny fan, as I'm used to the set-up where Phil Harris is the local drinker and skirt-chaser to contrast against Benny. Just as the radio program realized it was occasionally very funny to have Harris play against his type by taking a feminine role, the film takes the not-very-masculine Benny and places him in a role meant for a stronger, alpha male type, except the latter doesn't fit.

Of course, Benny isn't English either, which is the other odd part about him being cast in the film. Jack uses an exaggerated accent on the word "can't" (ie, "cawn't") throughout the picture, but that's about as much effort as he makes to sound English. Once you start to notice the accent, it actually becomes very funny, so much so that I wonder if Jack was doing it intentionally, much like his broad attempts at caricatured accents on the radio...and I wonder if the director knew what Jack was doing.

Charley's Aunt isn't terrible, probably because of the original source material. It's odd, but it isn't Jack's worst film.

George Washington Slept Here (1942) is a frustrating picture - frustrating because it comes so close to working. The film features Benny and Ann Sheridan as a couple who purchase a dilapadated old New England manor with supposed ties to the Revolutionary War and attempted to fix the place up until it's fit to live in, but along the way they suffer monetary troubles, family growing pains and accusations of infidelity. So, it's Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House then, isn't it?

Unfortunately, just about everything Blandings did right, George Washington gets wrong. Too many of the jokes are delivered in an episodic manner, instead of being tied to the overall narrative, as in Blandings. A sub-plot about Benny's cousin joining an acting troupe goes a long way for a very slight payoff. A bratty kid is introduced who is so bratty that he drives you to distraction (ie, "why am I watching this film? can't I find a better distraction?). The family's rich uncle leads to a few good comedy routines, particularly as he tells an old anecdote with Benny correcting him on various details, yet claiming he hasn't heard the story before.

Probably the biggest misstep is in the climax; facing foreclosure, the family is saved when they unearth an old boot which contains a long-lost speech written by George Washington, validating the old claims about the house. Reciting the speech stops the comedy dead in its tracks and while the speech gives the family the capital they need to keep the house, it's not as strong as the resolution to Blandings, where the family solve their problems through their own ingenuity rather than a deus ex machina. George Washington Slept Here is my least-favourite of Benny's pictures.

Of course, the most infamous picture Benny ever made was the Horn Blows at Midnight (1945), a movie he mocked for so many years (decades?) that you would suppose it were something truly terrible. It's a picture with some serious troubles, but it's not that bad. Jack plays a musician who dreams he's an angel who's been charged with going to Earth and playing four notes on a celestial trumpet at the stroke of midnight which will usher in the end of the world; unfortunately/fortunately, various parties get in his way, including a pair of fallen angels who have taken up residence on Earth and don't want to see it go away.

The Horn Blows at Midnight was allegedly a box office bomb, hence Jack's many jokes about the film's quality. I can believe this film would have had trouble during its release. The movie's entire premise is that the protagonist is having a dream; how are you supposed to entertain an audience who know dreams "don't matter?" Unlike, say, Buster Keaton's Sherlock Jr., it isn't fanciful enough to make the dream worthwhile, despite the director's efforts. Raoul Walsh was the film's director and he was a top-drawer talent; early scenes set in heaven with thousands of angels playing instruments are gorgeous, particularly one shot which flies over the orchestra. Walsh clearly made the film with a bit of love, so there are some things worth seeing in the picture. The other really fine bit in the picture is a waiter played by John Brown who is a typically entertaining John Brown character.

Outside of the visuals and the performances by Benny and Brown, I can't say much in favour of the Horn Blows at Midnight. Even moreso than George Washington, it feels like a collection of sketches. There's a thief, his ladyfriend and strongarm clinging to the edges of the story, along with the fallen angels, Benny's love interest, Benny's boss, a hotel detective, a wealthy dowager and about a dozen even less important characters. Strangely, the radio adaptation works in about every way this picture doesn't; the radio version dispenses with the business about the dream and instead of coming up with humourous reasons why Jack is distracted from blowing his trumpet, has characters argue for humanity's survival, until Jack himself is convinced. The Horn Blows at Midnight shouldn't have been a Warner Bros. picture - it really belonged at Columbia, where Frank Capra could've had a chance at making it cohesive.

At any rate, the radio version is keen. You can download a copy via the Internet Archive.

No comments:

Post a Comment